Good intentions

Writing content for artists is my job. I do it fast and I enjoy it most of the time. As I hate conflits and live in the constant fear that people would be offended because of me, exhibition texts are my favorite. It’s the opposite from being an art critic -which I sometimes do as well. I have no choice but being laudatory. The artist is happy -if he isn’t I’ll write it again and again until he’ll be. I’m pleased to see him happy. The viewers get a better understanding of the artistic process at stake. And, most importantly: no one gets hurt

Over the course of the last years, I wrote many texts for Benjamin Mecz’s projects and ,exhibitions. I first did it out of friendship. On the corner of a coffee place table in south Tel Aviv I hand wrote him a proposal for the application to the White Night in Paris. He got the gig. I was then since two years the artistic manager of a gallery in Tel Aviv. I was happy there, but I had a sense of longing for the emulation, excitement and risks that I wasn’t taking with my career. For months, Benjamin tried to convince me to quit my job and start as an independent exhibition manager and curator. I was terrified, but when I finally did so, Benjamin -as a thank you present for his legendary obstinacy- was the first I signed as a gallery artist. He was as well the first artist .I exhibited in a solo show, and my first sale was a work by him

Long story short, I wrote many texts for Benjamin and I owe him big. But, a few days ago, when asked to send a piece about his work for an issue on the theme of “parting”, I went totally dry. I experienced a writer’s block for the first time. I read the previous texts I had written for him, I .looked up at my images folder of his works to try and find something relevant to say. Nothing

The bond

I took me a while to realize that if I couldn’t find anything to write, it was for the simple reason that Benjamin’s artworks and the notion of parting are incompatible. Rather than dividing .between elements and people, Benjamin’s practice was all about uniting

Benjamin Mecz, T³ , 2014, 132 T-shirts, 360 x 360 x 490 cm, White Night, Paris

T³ , 2015, is a sculptural installation made of 132 white basic T-shirts, sewed together, and stretched in the form of a cube by the most ordinary kind of polypropylene twine. In short: a simple geographical shape, made out of simple materials. The text accompanying the work writes that this installation is “more about assembling than sewing together”, which therefore creates solidarity

In this work, harmony comes from transforming an individual and universal object into a gigantic and collective piece. In other words, a T-shirt is only a T-shirt, but when 132 T-shirts join forces, union becomes art

The same process is at stake in KNULP, the above-mentioned solo exhibition I organized with Benjamin. The performance / installation took place in october 2015, in the courtyard of one of Paris’ most beautiful libraries

Benjamin Mecz, KNULP , white canvas and paper, 2100 x 950 cm, Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, 2015

KNULP consists of 200 square meters of canvas Benjamin sewed together during the course of two months and laid down in the courtyard of the library. The white on white canvas recreates ,the cover of the eponym novel Knulp by Herman Hesse, that Benjamin found in a street of Paris and for which he grew a fascination. In Hesse’s novel, Knulp is a lonesome wanderer. He lives and dies alone. Benjamin aimed to transcend the hero and pay him his respect by bringing as many people he could around, and on, the artwork

During the four day long performance, people were invited to walk on the canvas in order to soil it -interestingly enough, most visitors didn’t dare to “touch” the artwork, I doubt it would have been the same in Israel. Obviously, they couldn’t know they were creating the artwork by the mere fact of being there . By the end of the exhibition, most of the canvas was blackened, only the word KNULP stood out, white as snow

Togetherness

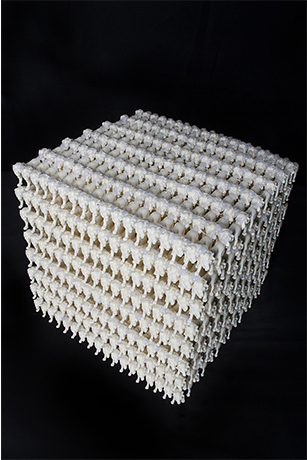

Benjamin Mecz, Mille Lions , 2014, plastic and glue, variable dimensions

The connections created by the seam, the solidarity of those simple elements assembled define Benjamin’s ethos as an artist. That is why I can’t think of parting when I reflect on Benjamin’s works. May it be in the materials, or in the way he considered his practice, he was all about community and togetherness. As utopist as it may sound in our individualistic current conventions, Benjamin foresaw his artworks as a collaboration and a collective adventure, with

.other artists, and his public

His decision of coming back to Israel two years ago was related to that ideal. I didn’t always agree with him, but Benjamin felt a bigger solidarity in the Israeli art community. He might have felt this way because the scene is smaller than the Parisian one. I believe it is rather that with much less public subventions, galleries and initiatives than in Europe, the Israeli artists are forced to get together and create their own opportunities, exhibitions and collaborative spaces

,Benjamin invented a play on words to describe that feeling: “terrain vague / nouvelle vague” which means wasteland / new wave

This way of seeing art as a communion reminds me of one of his early works, “Mille Lions” ."another play on words: “A Thousand Lions”, which, when said very fast sounds like “Millions" As we say in French L’Union fait la force – Unity is strength